When we think of Italian Renaissance painting (let alone Renaissance art in general), the name of Masaccio does not usually make it quite up the ranks. And yet, the likes of Leonardo, Michelangelo and Raphael would not have become who they were had it not been for the work of this ‘precocious’ artist.

Why precocious? Unfortunately, Tommaso di Giovanni Cassai (aka, Masaccio) died in 1428, aged barely 27. However, in the span of just five-six years (when the artist was in his 20s) he revolutionised Italian painting, kickstarting that process better known to us as ‘the Renaissance’. How did he do that? We are going to discover this by analysing four of Masaccio’s still-extant masterpieces. But first, let’s have a brief look to his life.

A short, humble life

Tommaso was born in 1401 in San Giovanni Valdarno, not far away from Florence. His father, Giovanni, was a notaio (a sort of ‘public solicitor’, peculiar to the Italian system), but died suddenly in 1406, himself aged only 27. The clerical nature of Giovanni’s job meant that the family was quite well-off for the time, if not super rich. Tommaso had a brother who was born after their father’s death, nicknamed ‘lo Scheggia’ (i.e., ‘the Splinter’), who himself became an accomplished painter later on.

The famous art historian Giorgio Vasari (himself a Renaissance painter) informs us on the origin of the peculiar nickname given to Tommaso during his lifetime: the name Masaccio implies a disregard for the way this young lad presented himself and cared for worldly affairs, such as collecting debts from his debtors. In Italian, the suffix -accio is usually attached to words to give them a pejorative connotation. ‘Mas-‘ stands for the shortened version of his birthname, Tommaso: hence, we can roughly translate the nickname as ‘bad/scruffy Thomas’.

Masaccio’s activity is distilled in very few years between 1422 and 1427, during which he mainly worked in Florence and surroundings. In just five years, he applied some of the contemporary theories then in vogue in architecture and applied them to painting, completely revolutionising it. Let’s have a look at four of his surviving key artworks and let’s try to understand what he did that was considered astonishing even for the time.

Masaccio’s four Renaissance masterpieces

La Cappella Brancacci (Brancacci Chapel)

Masaccio collaborated with the elder painter Masolino da Panicale (ca 1383–1447) for this commission. The frescoes depict stories from the Bible and from the life of St Peter and were left incomplete because of the two artists’ departure for Rome in 1428, a few weeks before Masaccio’s own death.

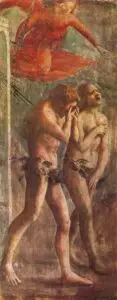

To understand the way in which Masaccio’s painting differed from his older collaborator’s we can compare their two scenes depicting Adam and Eve, which front each other at the entrance of the Chapel. In Masolino’s painting (above), the figures are still expressionless and quite formal in their movements. Not so for Masaccio’s: in his depiction of the first human couple being chased out of the Garden of Eden (below), the young painter’s figures express all the drama of the moment and the grief at their mistake. Moreover, showing the figures from a ¾ perspective rather than from the front like in Masolino’s scene gives them a sense of a tridimensionality which is absent from the older painter’s scene.

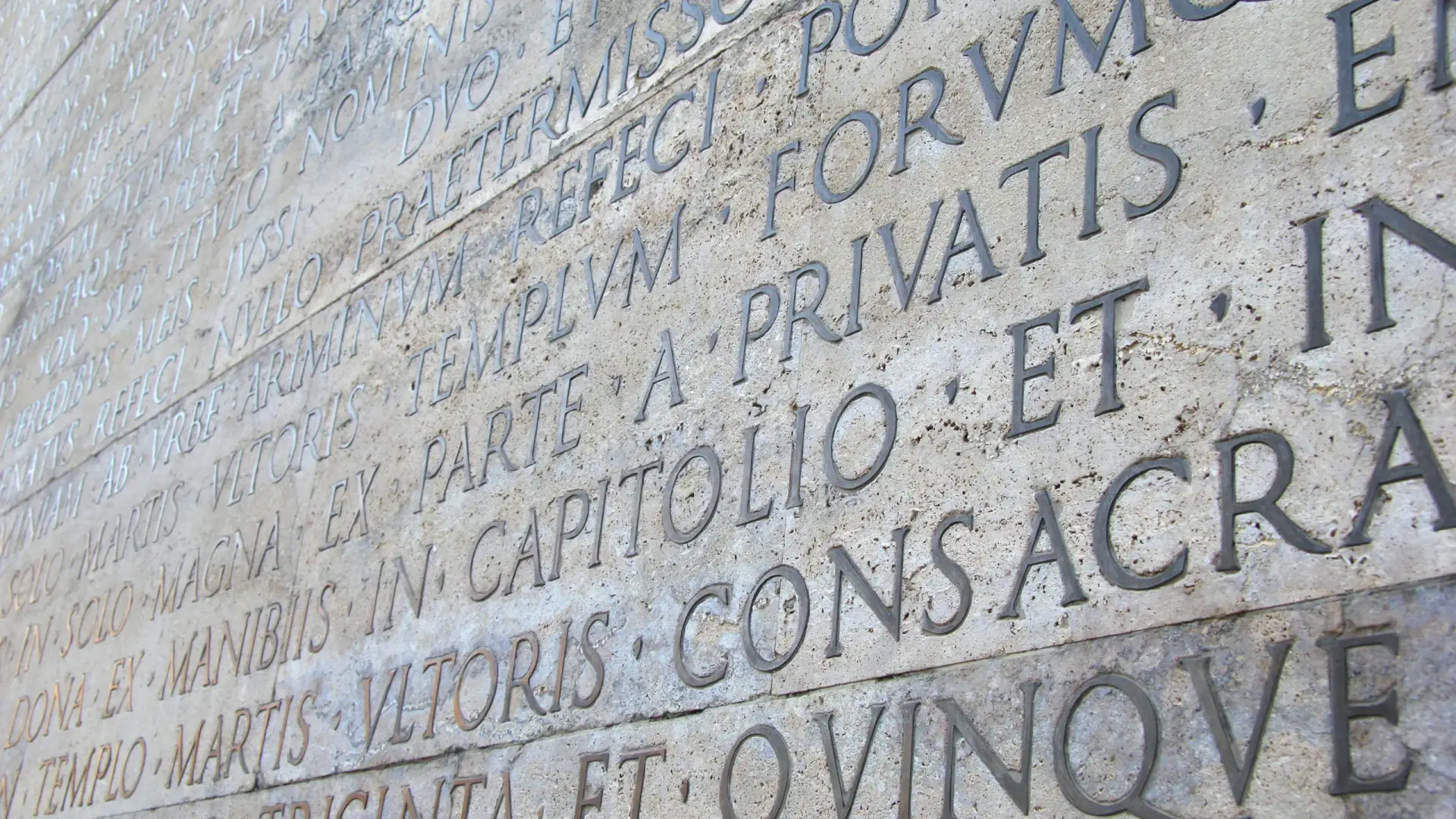

Masaccio’s inspiration for such novelties derived from the work of two great Florentine artists: Giotto (ca. 1267–1337) and Filippo Brunelleschi (Masaccio’s contemporary). Both these people had innovated their respective fields — i.e. painting and architecture — by introducing the concept of perspective (‘la prospettiva’) back into art. This involved the introduction, in a painting, of geometrical forms and of a rational conception of the space.

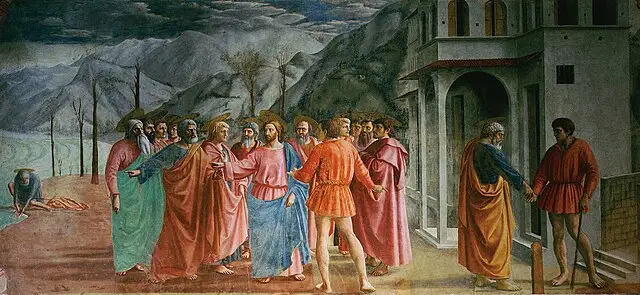

An example of perspective in act in the Cappella Brancacci can be seen in Masaccio’s Tribute scene (‘il Tributo’), where St Peter pays off the taxes to the tax-collector on behalf of Jesus (right). If you pay attention, you will notice that both the building on the right and the apostles’ faces are all converging towards a central, focal point (‘punto di fuga’): this is Christ’s head — an element which cunningly plays on the Christian nature of the commission too.

Madonna in trono con Bambino (Enthroned Virgin with Child)

This panel was originally part of an altarpiece which Masaccio depicted in 1426 for ‘la Chiesa del Carmine’ in Pisa. In this painting, the point of view is quite low: it rests in between the two angels in the foreground.

The Madonna and the throne where she sits convey a sense of profundity (‘profondità) which is lacking in earlier, medieval depictions (think about Masolino’s scene above). Very innovative is also the depiction of Christ’s halo (‘l’aureola’): for the first time, this is depicted obliquely, rather than frontally as usual. This element of perspective enabled Masaccio to put the child’s head more in evidence from its background.

However, it is still the early 1400s, after all; medieval elements such as the golden background (‘lo sfondo dorato’) and the surrounding angels (‘gli angeli’) are still present.

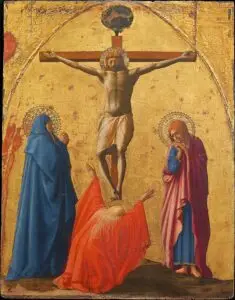

La Crocifissione (Crucifixion)

This painting too was part of the same altarpiece in the ‘Chiesa del Carmine’ of Pisa to which the ‘Madonna’ above belonged. Here, Christ on the cross acts as the central axis (‘l’asse centrale’) of the composition. Every other figure’s position (the Madonna on the right, St John Evangelist on the left and Mary Magdalene in the foreground) is not casual: together, the four characters form a pyramidal structure whose top is, once again, Christ’s head.

Remember that sense of drama (‘la drammaticità’) that we noticed earlier in the Cappella Brancacci? The open arms of Mary Magdalene in this scene are a striking example of the expression of that same feeling.

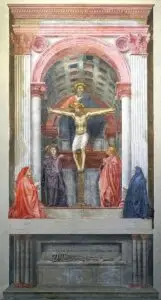

La Trinità (Trinity)

For the last two years of his very short life (1426–1428) Masaccio was busy painting ‘La Trinità’ in the ‘Chiesa di Santa Maria Novella’ in Florence. This composition showcases all the young Masaccio’s mastery of the brush.

The figures are encased within a solid, realistic architectural frame which conveys the sense of perspective and recalls elements of the Classical world which were being rediscovered at the time. Particularly effective is the rendition of the vault (‘la volta’) which is supported by Ionic columns.

The two commissioners of the scene (unknown) are shown kneeling at either side of the Crucifixion scene. In order not to break the realism, Masaccio adopts here another innovation: for the first time, real humans are depicted in the same size of the holy figures, rather than being painted smaller, as usual. This element alone encapsulates the whole philosophical idea behind the Renaissance: it is man which is at the centre of the universe and of study now — not God anymore.

Once again, all the figures are encased in a pyramidal structure — created by perspective — which has its focal point (‘il punto focale’) in God the Father’s head.

Curiosity: the fresco survived in its original location and was rediscovered in 1860 during refurbishment works, when the altar in front of it was removed.

Would you like to know more of the Renaissance? Or perhaps would you like to learn some basic Italian that even Masaccio understood?

It is incredible how the young Masaccio was capable of producing so much in so little time and one is left to wonder what else he could have accomplished had he lived longer.

Would you like to know more about Masaccio, his life and his other extant works? You can explore my cultural courses (https://www.thetuscantutor.com/cultural-courses/) or Contact Us | The Tuscan Tutor to book a free intro lesson to begin your journey in Italy’s rich past and discover the wonders of the Italian Renaissance.

Or perhaps are you more interested in understanding how Masaccio spoke? After all, the modern Italian language has its roots in the Tuscan ‘dialect’! Are you curious to know the difference between ‘la prospettiva’ and ‘il punto’? Why do Italians say ‘la’ but then use ‘il’ with another word? You can check my language courses page (https://www.thetuscantutor.com/language-courses/) to learn this and much more!

Where can I see Masaccio’s paintings?

Cappella Brancacci – Chiesa di Santa Maria del Carmine, Firenze

Crocifissione – Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Napoli

Crocifissione di San Pietro – Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

Madonna del solletico – Uffizi, Firenze

Madonna in trono – National Gallery, London

Martirio di San Giovanni Battista – Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

Santi Girolamo e Giovanni Battista – National Gallery, London

Trinità – Chiesa di Santa Maria Novella, Firenze